Recuperative heat exchangers, but for your face

November 30, 2025

Winters here often go below -30 degrees Celsius. Along with goggles and a ski mask, I recently found out about heat exchanger masks to improve airway comfort.

I tried the now-discontinued Polar Wrap masks mentioned in that article, and while it helped, it was pretty annoying to use. I ended up designing my own full-face heat exchanger mask to maximally solve this:

I look very silly wearing this, but it has some features that make it unusually useful for the extreme cold!

The Problem

Existing heat exchanger masks all use a regenerative design - warm exhaled air passes through the heat exchanger and warms up a regenerator (usually a metal mesh or heatsink with a large surface area), then cold inhaled air later passes through in the other direction and takes the thermal energy from the regenerator. With the Polar Wrap, this essentially takes the form of a long impermeable cloth airway filled with copper sponge:

This design has two major problems:

- There’s dead space inside the heat exchanger, which traps stale exhaled air that you’ll later inhale again. The amount of dead space increases as the regenerator heat capacity increases, so the colder the weather it’s designed for, the more stale the air will be inside with each breath. Also, when you’re taking smaller breaths, a larger fraction of the air is stale.

- Exhaled air is cooled down by the regenerator and condenses its moisture inside. Eventually, this allows bacteria to grow in the same space that you’re inhaling air from. To somewhat mitigate this, most heat exchanger masks are made from copper (which has excellent antimicrobial properties), or recommend washing after each use. Some are even dishwasher-safe to make this more convenient!

That said, regenerative heat exchangers are also cheap and highly manufacturable, and the efficiency is fairly high since the warm air travels in the opposite direction to the cold air. It makes sense why all of the existing products on the market take this approach.

For fun, I wanted to see if a recuperative heat exchanger could be equally effective while solving those two problems, and to see if a recuperative design could also solve the issue of goggles/glasses fogging up from perspiration.

Design

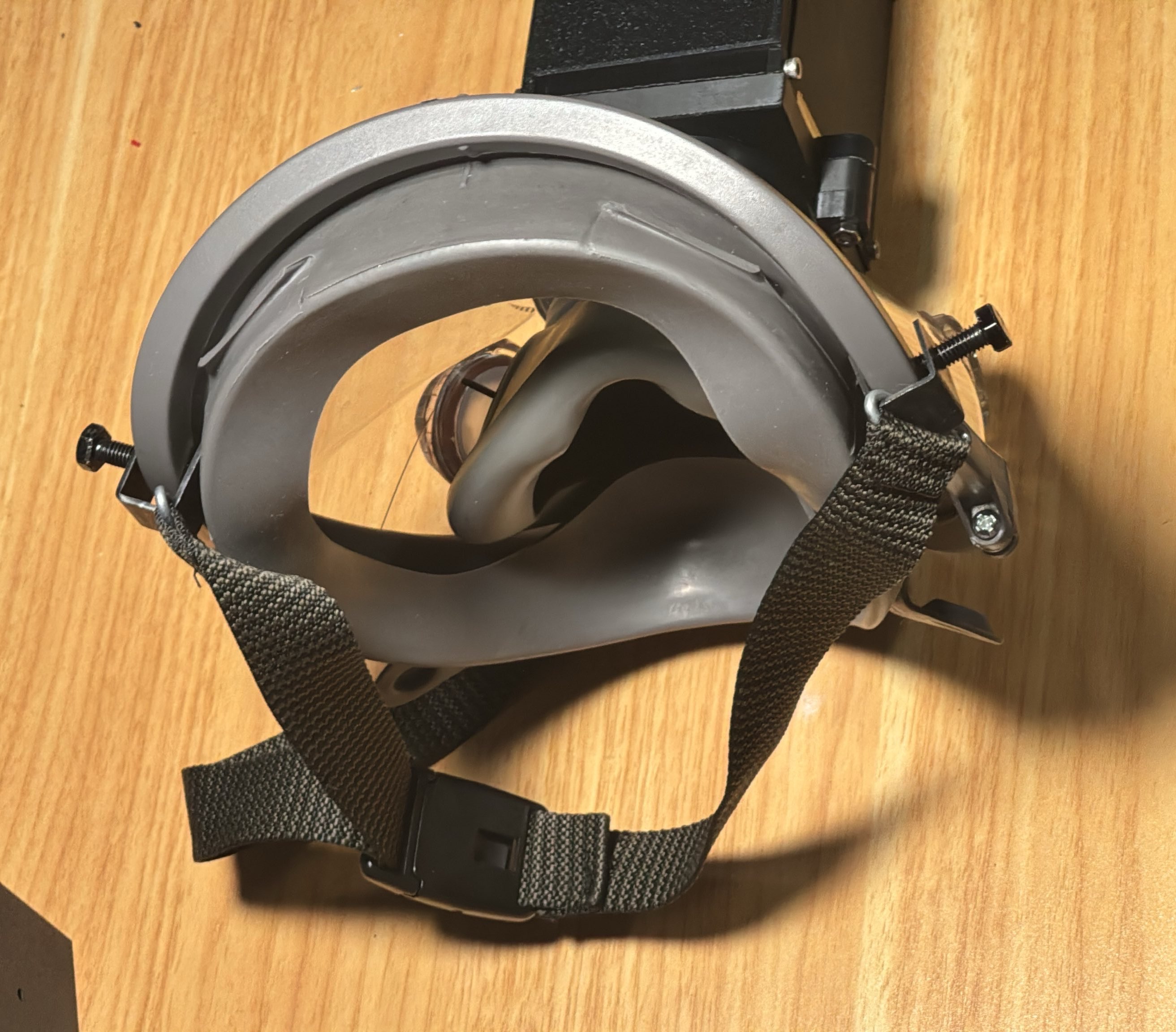

First, I started with a $26 AliExpress knock-off of the 3M 6800 full-face respirator:

Just to be clear, you should never use these knock-off respirators for actually protecting your respiratory system. The seals and valves on this one all leak slightly, and the quality is noticeably lower compared to a genuine 3M 6800. We’re only using this here because these small leaks don’t matter for this project, and it costs 10 times less.

The front of the respirator has a NATO 40mm (STANAG 4155) threaded port for a filter cartridge (in the image above, shown with the cap installed). When you inhale, air enters through the NATO 40mm port, passes through a one-way valve (the thin blue flap in the image below), then enters the clear face shield area through two slots on the inside. This keeps the humidity inside the face shield at ambient levels, and prevents the face shield from fogging up in the cold when you’re sweating.

The inhaled air then passes through two one-way valves into the mask portion of the respirator (the black circle in the image above), which covers your nose and mouth. When you exhale, air exits through another one-way valve and out through the exhaust port, located above the NATO 40mm port on the front:

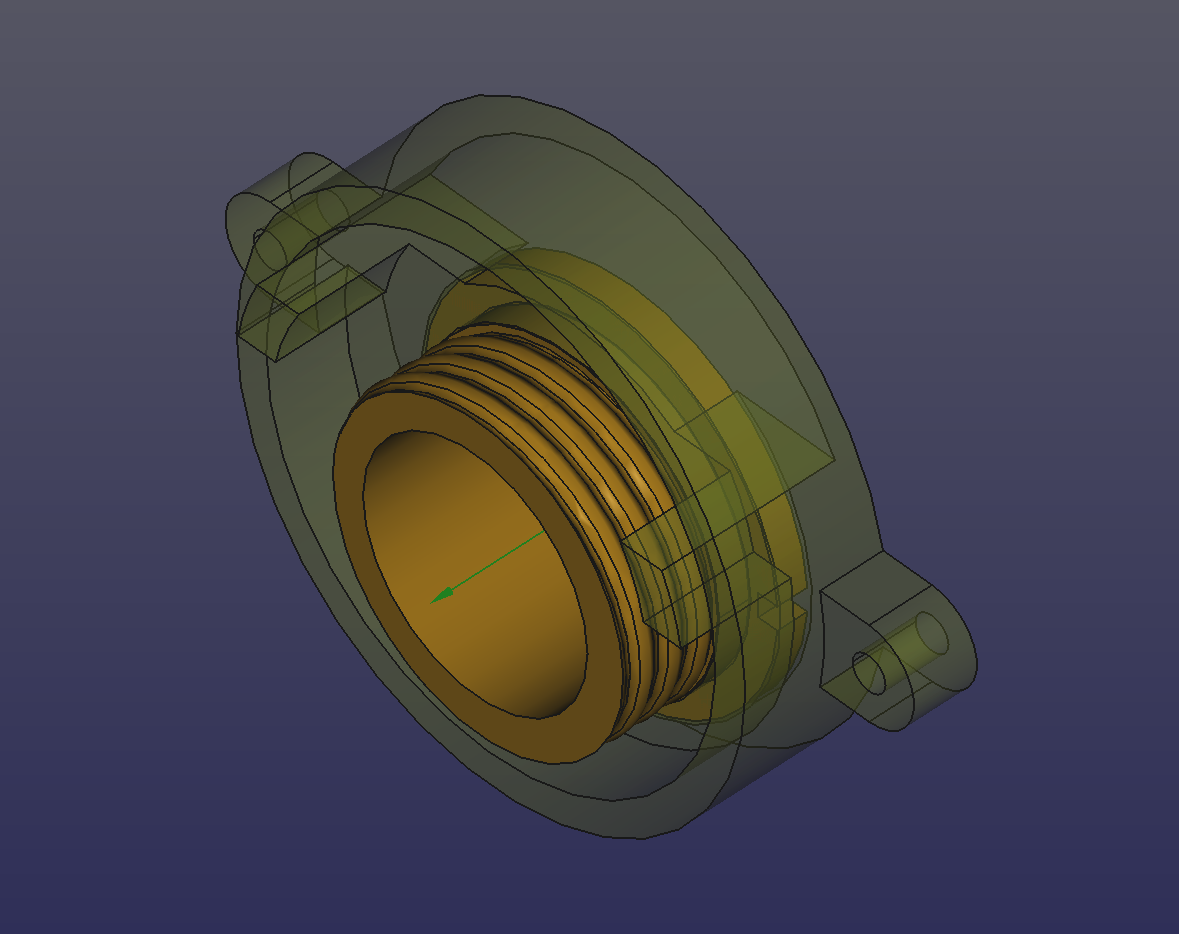

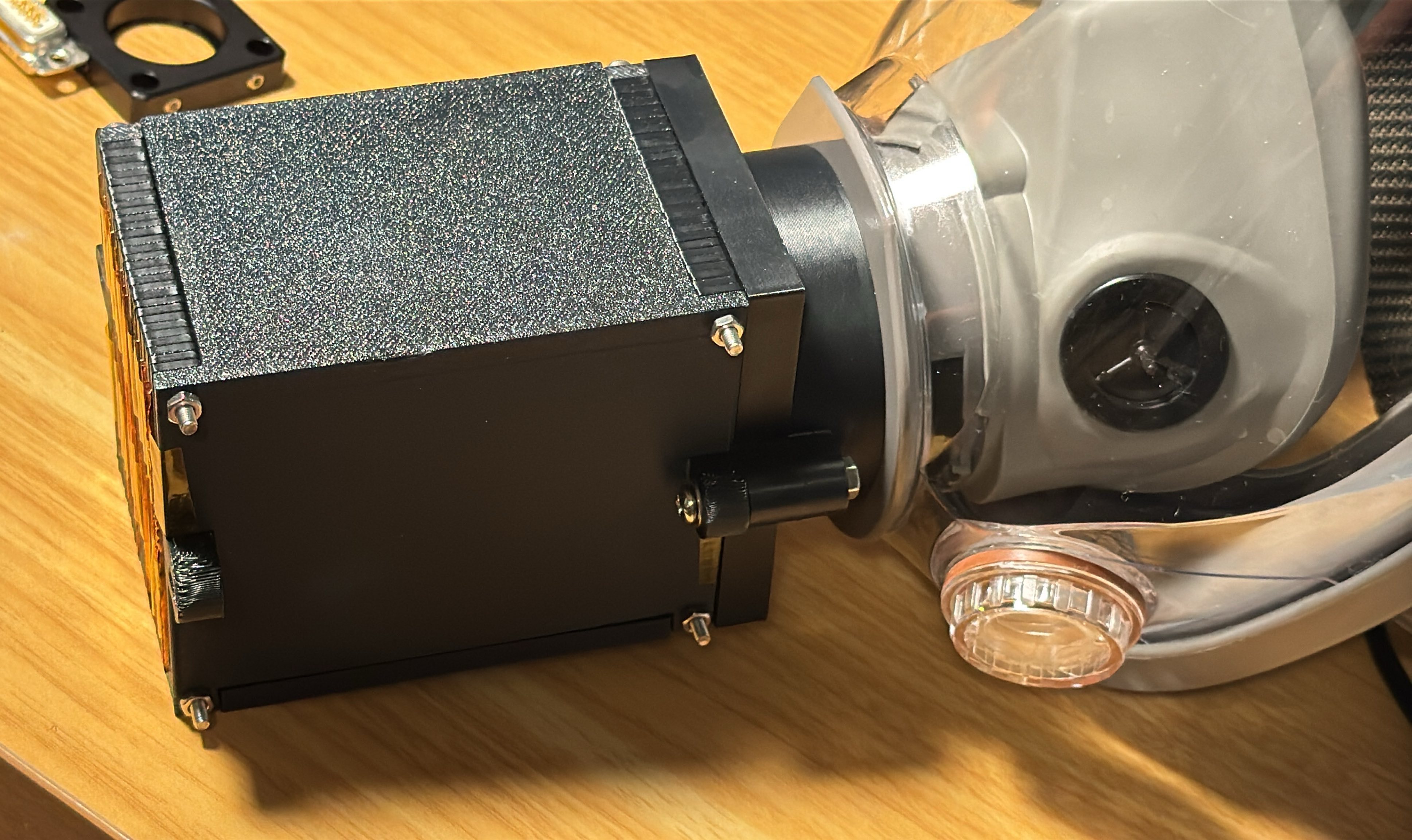

The recuperative heat exchanger requires us to separate the inhaled air stream from the exhaled air stream, so it’s very convenient that the one-way valves built into the respirator already do this for us. I designed an adapter to non-destructively attach onto the front of the respirator by screwing into the NATO 40mm port for inhaled air, and mating with the exhaust port for the exhaled air:

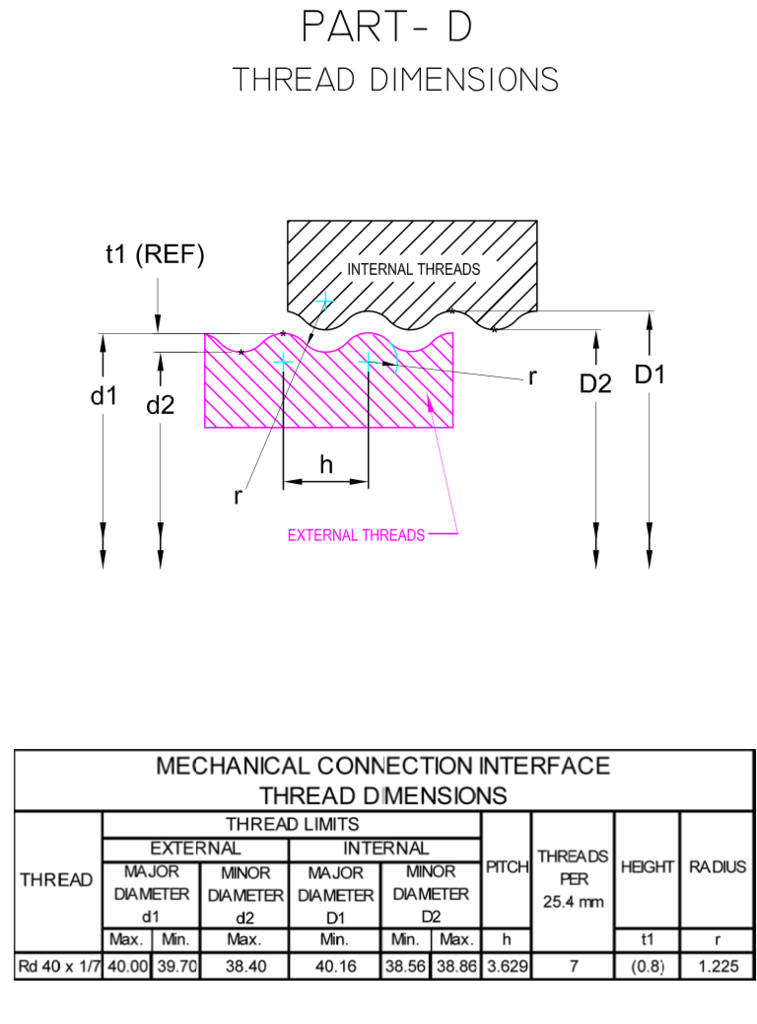

It’s surprisingly difficult to find a good technical drawing of this thread profile, but this Hackaday.io project was a really valuable reference:

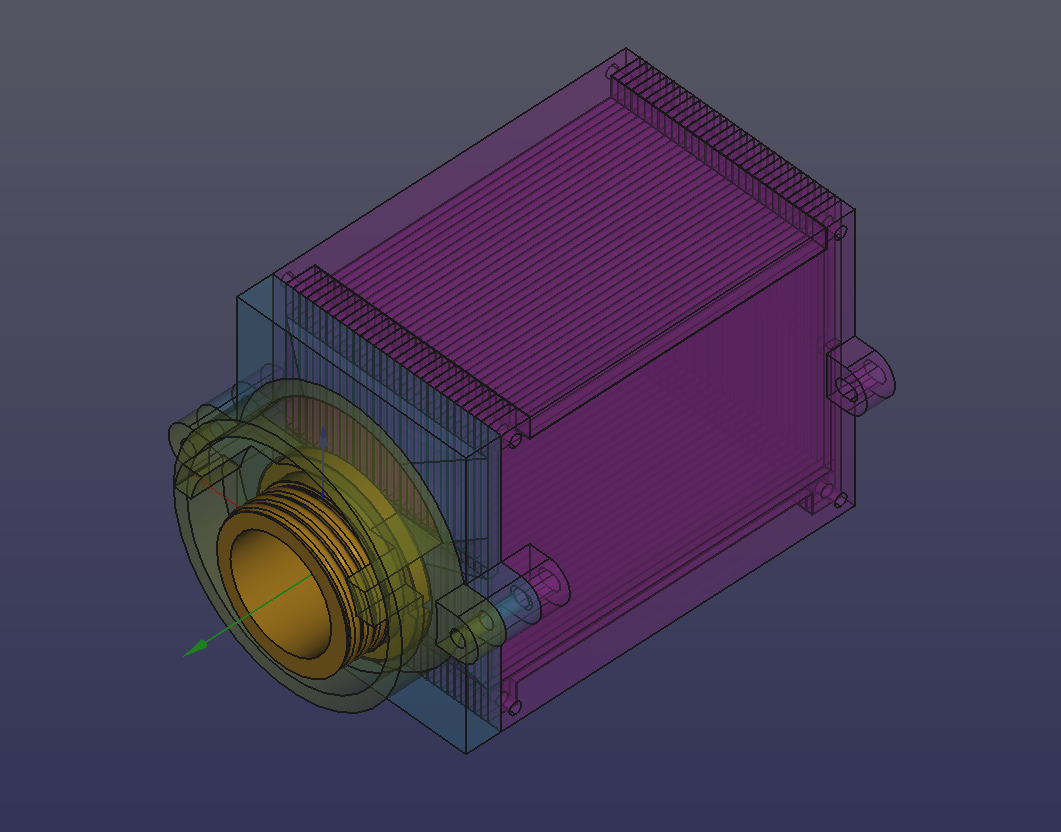

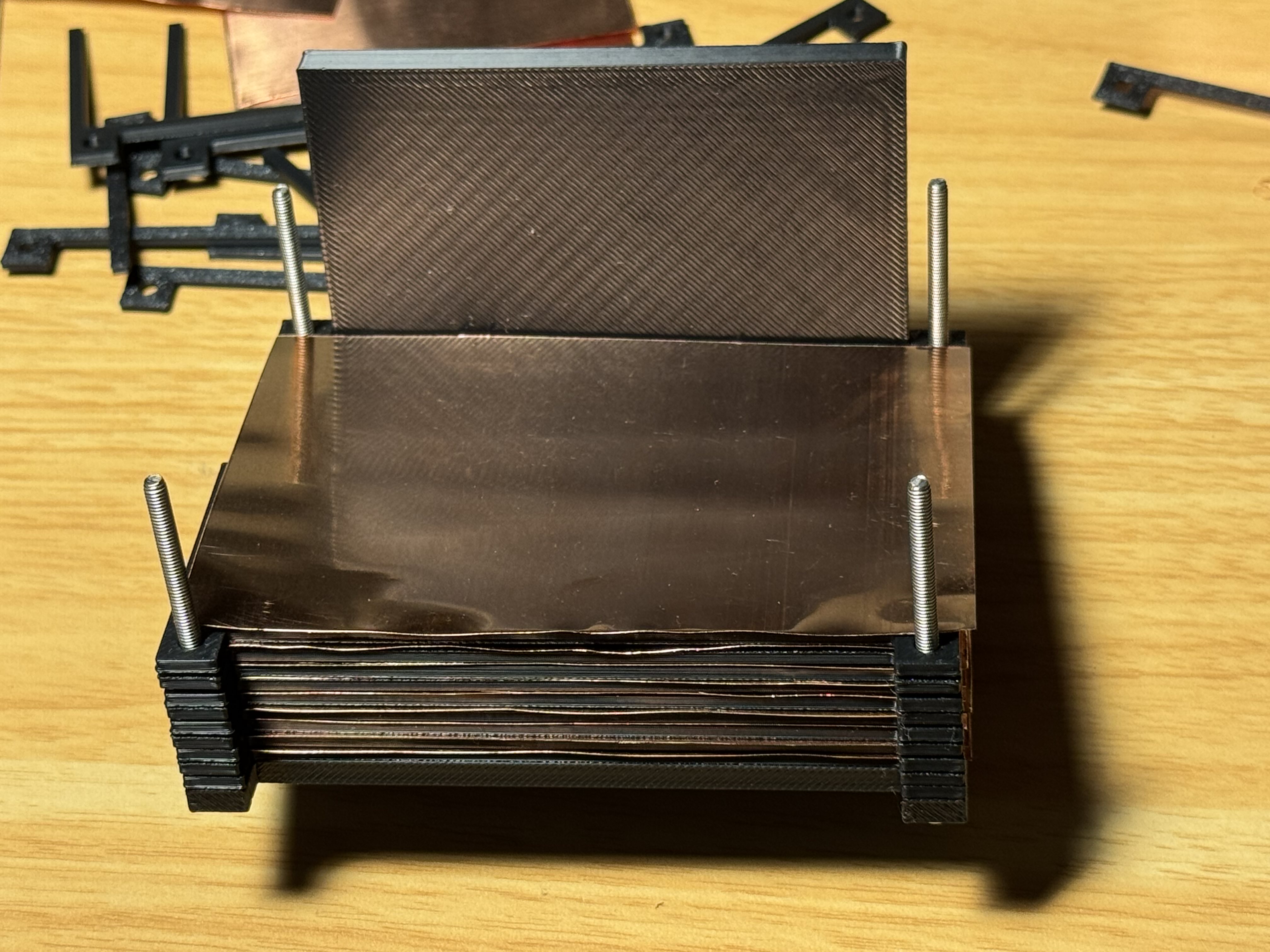

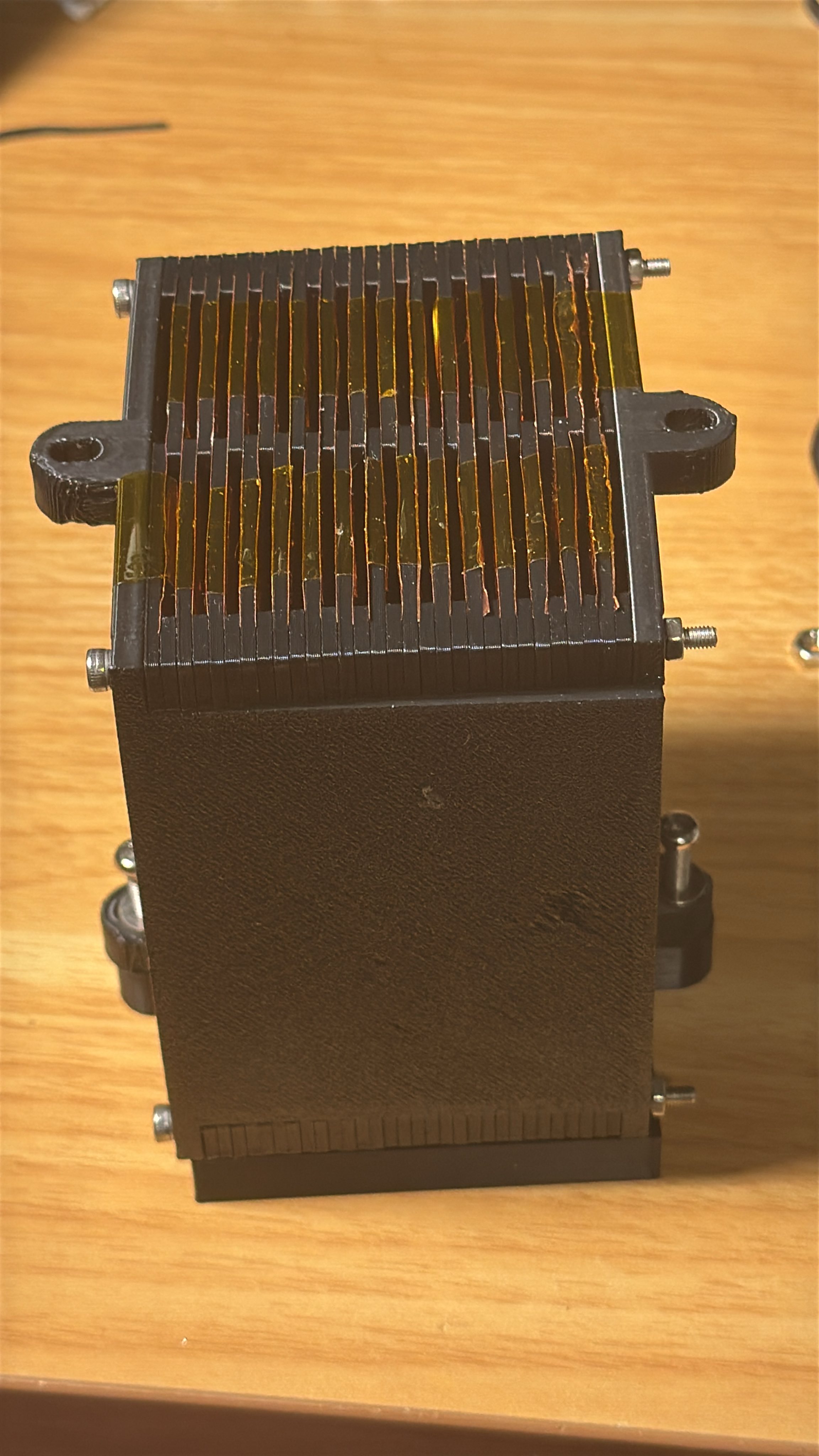

For the heat exchanger, I modelled a stacked-plate counterflow design to attach to the adapter via two bolts. It’s basically a box that holds a stack of thin copper plates (as thin as possible to reduce thermal impedance, but not so thin that it’ll flex out of shape from the air pressure differences), with alternating “left-to-right” and “right-to-left” 3D printed brackets:

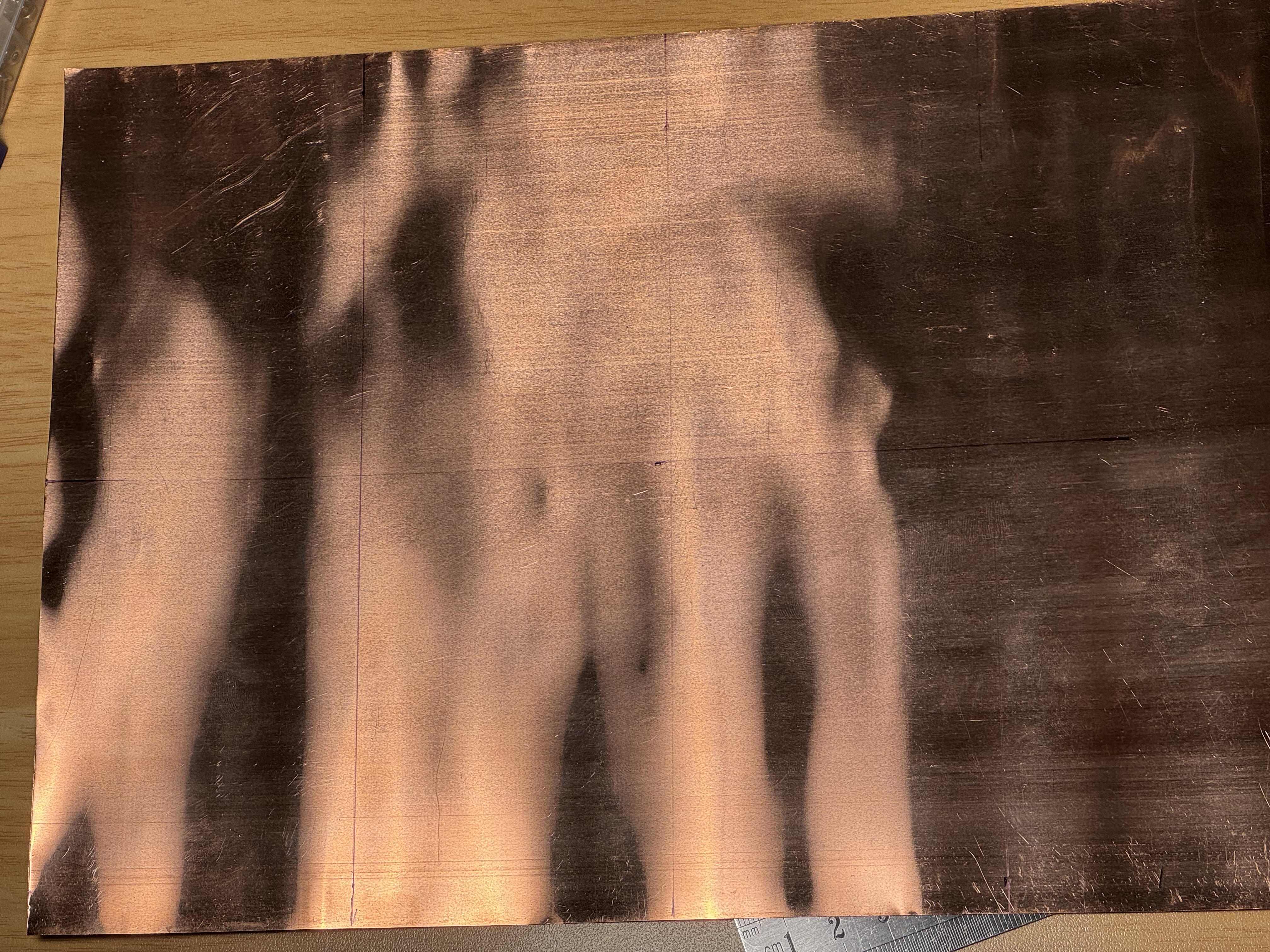

The copper plates are 70mm by 100mm and 0.1mm thick. I don’t have a usable fiber laser at the moment, so I purchased two rolls of 0.1mm thick, 2m by 100mm copper sheeting, and cut out all the heat exchanger plates by hand with scissors:

Then, assembling the heat exchanger by stacking 30 pairs of brackets between 29 heat exchanger plates. The only other unusual parts I needed for this were 75mm-long M3 bolts:

One issue I had here was that the heat exchanger plates weren’t very flat, and so there would be gaps between the brackets and the plates that would leak air in the wrong direction. It took a lot of time bending them back into flat sheets, and even then it still wasn’t perfect! Next time, I’d probably purchase the copper in flat sheets rather than as a roll. To temporarily fix this, I taped the gaps shut:

Surprisingly, the tape ended up holding together well even in the cold, so I didn’t end up replacing this with a more permanent solution like gluing the plates to the brackets. Finally, we can attach the heat exchanger to the adapter:

The respirator’s default head straps were annoying to put on and take off, since they’re designed to secure the respirator to your face without leakage. Since we don’t care about small amounts of leakage, I wanted to replace them with something more comfortable. There weren’t any straightforward ways to attach anything to the sides of the respirator, so I got these small screw clamps intended for securing mud flaps to a car (these have a jaw width of about 15mm, but anything between 14mm-20mm would probably work):

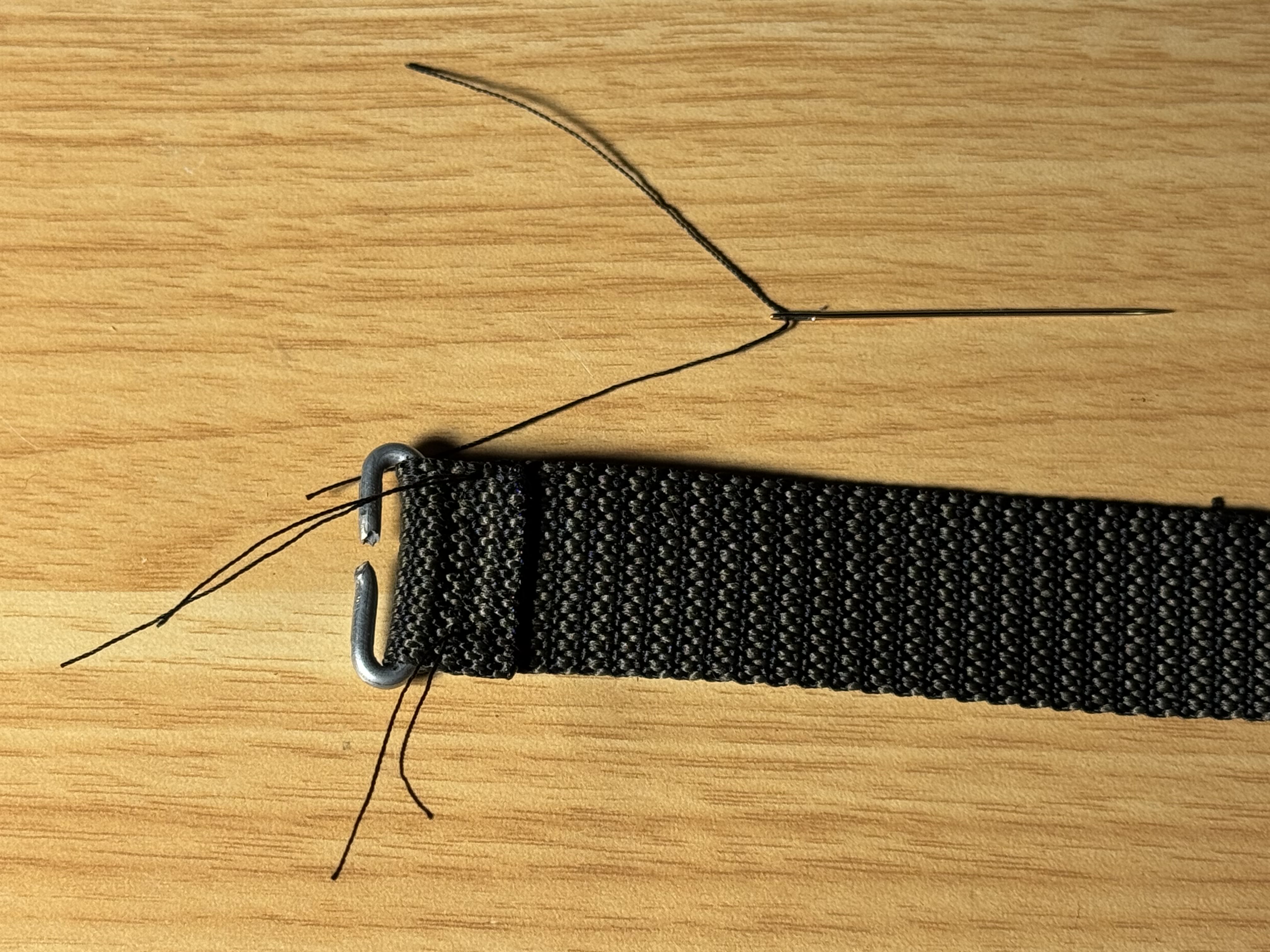

I then found an old nylon belt, cut it in half, and sewed the cut ends to two metal clips I bent out of 10 gauge steel gardening wire:

The clips then can be slid over the small screw clamps, and then clamped to the sides of the respirator. Now, the respirator can be put on, taken off, and adjusted using the belt’s original quick-release buckle:

You could probably also accomplish the same thing without any sewing or wire bending, using something like a standard backpack chest strap.

Results

I realized that the most likely reason this idea isn’t commercially popular is that these heat exchangers are difficult and labor-intensive to build. Just aligning all of the plates and assembling them correctly took nearly an hour of manual work, not to mention the sealing step with tape. Commercial heat exchangers are usually made of stacked plates that are brazed together, and often have between 30-90 plates at a spacing of 3mm-5mm in water-to-water units, compared to the tighter 2mm plate spacing used in our design. These sell for around CAD$100, so I’d estimate our design would cost around CAD$130 even at quantity. My intuition is that it’s possible to get this down to CAD$100, but that’s still a lot more than existing heat exchanger masks on the market.

It’s a balmy -10 degrees Celsius out, so we’ll have to wait for the winter to get colder before the real test begins! But I did get a chance to do a 1 hour outdoor test at low exertion.

The in-mask temperature after 30 minutes was 24 degrees Celsius above ambient, compared to 21 degrees Celsius above ambient from the Polar Wrap. The in-mask temperature depends heavily on ambient temperature/humidity, as well as the wearer’s exertion level, but I predict that -30 degrees Celsius ambient temperatures would be quite comfortable when wearing this.

Originally, I was concerned about ice buildup on the exhaust side of the heat exchanger, but it seems like this isn’t an issue due to heat leakage from the warm side to the cold side. This keeps condensation liquid while it’s in the heat exchanger, but it quickly forms icicles after it drips out of the exhaust outlet.

A big benefit of this design is that the clear part of the mask never fogs up, since the warm air from the heat exchanger has the same moisture content as the outside air. This was my number one complaint about winter goggles, due to often having to stop and clean them. The full-face shield also maintains peripheral vision better than most goggles, and is fully compatible with wearing glasses underneath.

The big downside of this design is that it’s larger and heavier than the usual goggles/ski-mask/Polar-Wrap combination. However, it’s a lot easier to breath through compared to the Polar Wrap, with less air resistance and no staleness or coppery smell (probably because the copper stays dry on the intake side). The air resistance in this design is probably lower than needed - I would make the next version lighter and more compact by using 50mm by 100mm plates instead of 70mm by 100mm plates.

Make your own

To build your own full-face heat exchanger mask, you’ll need to:

- 3D print all of the parts shown in the FreeCAD design. I recommend polycarbonate for cold-temperature resistance, since ABS/PLA tend to get brittle below zero Celsius:

- Obtain these parts or their closest equivalents:

- 1x Knock-off 3M 6800 full-face respirator with NATO 40mm port in the front: option 1, option 2, option 3

- 29x 70mm by 100mm rectangles cut from 0.1mm thick copper sheet stock: option 1, option 2, option 3

- 4x M3 bolts, 75mm length: option 1, option 2, option 3

- 4x M3 nuts: option 1, option 2, option 3

- 2x M4 bolts, 30mm length: option 1, option 2, option 3

- 2x M4 nuts: option 1, option 2, option 3

- 2x mud flap C-clamps: option 1, option 2, option 3

- 1x backpack chest strap: option 1, option 2, option 3

- Assemble all of the parts according to the FreeCAD design and build notes above.